Escrow accounts have been used for many years by private fund managers and their investors as a safety net against the payment of carried interest that may ultimately be clawed back to be returned to investors. Combined with an end of life “clawback” test, an escrow account gives investors the comfort that the right amount of carried interest will be paid. However, the number of funds with escrow accounts has been reducing over the last six to seven years, as managers and investors look to other methods of reassurance that avoid money sitting idly in an account, potentially for several years.

Even in a fund with a “fund as a whole” carried interest, where all amounts drawn from investors must be returned, plus a preferred return, before the executives can start to receive any carried interest, there is a risk that carry could be paid to executives that ultimately belongs to the investors. The risk of a clawback of carried interest for these funds is less likely than it would be for a fund with “deal by deal” carried interest (where only the acquisition cost of the investment in question and the preferred return must be repaid, plus any acquisition costs of realised investments not previously returned to investors, and possibly amounts to cover any potential losses in the unrealised portfolio), but investors have still traditionally requested an escrow account even where there is a fund as a whole carried interest. However, while escrow accounts do provide security, they entail potentially large amounts of cash sitting in an account for several years (usually until a certain return test is met following which an overpayment of carry would be very unlikely). In addition, due to the tax transparent nature of many fund structures, tax is still payable by the carried interest holders on amounts paid into the escrow account, and tax distributions are usually made, which will reduce the pot of money available.

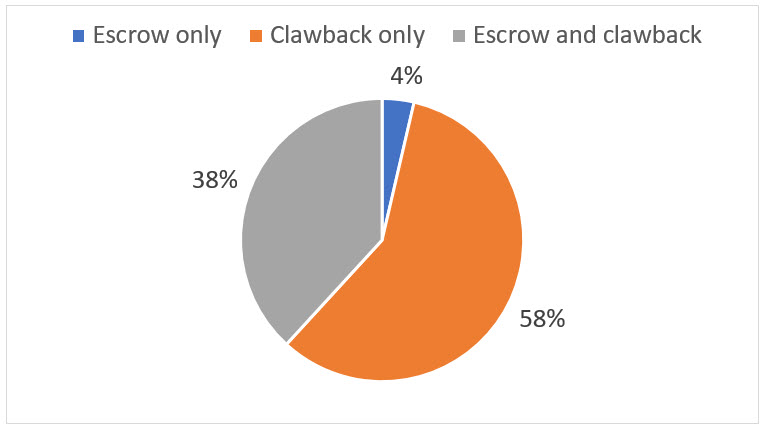

Goodwin’s recent private fund terms survey, covering 62 funds raised in the last 12 to 18 months, has shown that 58% of funds now have a clawback of carried interest, but no escrow account. This can be contrasted to the same terms survey in 2014, where only 30% of funds were in this category.

This reduction poses an interesting question about how investors are getting comfortable that amounts of carried interest paid to executives, rather than into an escrow account, will be available to be clawed back, should this prove necessary.

Funds with a deal by deal carried interest typically do not have escrow accounts (although some may have a partial or time limited escrow) as paying amounts into escrow somewhat negates the benefits of having deal by deal carry. They have traditionally looked to other methods in lieu of an escrow such as interim clawbacks (clawbacks at regular intervals throughout the life of the fund rather than a single test once the fund is wound up), personal guarantees from carry recipients or house guarantees from the manager/GP group. Those solutions have now become more common with funds that have a fund as a whole carried interest, and the Goodwin terms survey analyses the 58% of “clawback only” funds to see what additional protections they contain.

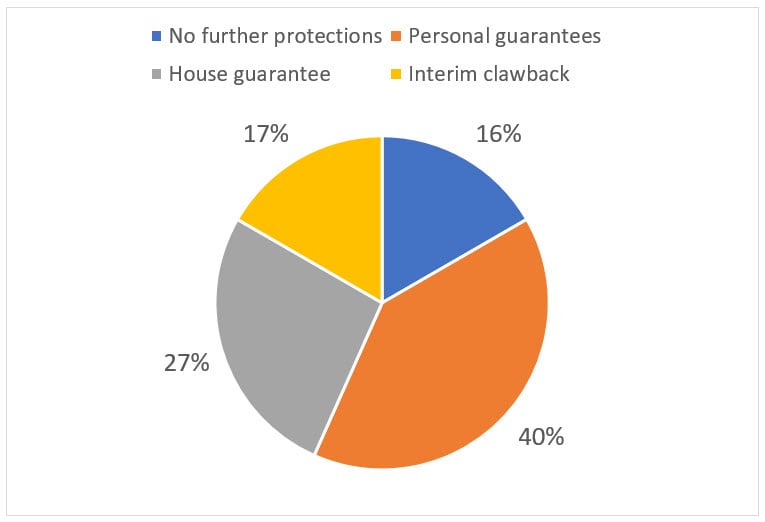

The chart below reveals that 67% of those funds have some sort of guarantee, with investors being able to make a claim directly against the carried interest holders through personal guarantees (40%) or against the fund manager through house guarantees (27%). 17% of the funds contain interim clawbacks – and just 16% have no further protections beyond the single end of life clawback test.

That is not to say that the investors in the 16% of funds with no further protections rely solely on an end of life clawback with no other remedies. It is likely that the carried interest holders have a contractual obligation to return amounts to the carried interest vehicle, albeit that the investors cannot enforce this obligation themselves and would rely on the house to bring a claim for failure to repay. It may also be the case that the carry vehicle in question is a single carry vehicle covering many different funds, and so it will have assets beyond just the amount of carried interest paid by the fund in question (which is almost akin to a house guarantee).

It is unlikely that the funds industry will see the end of escrow accounts, as there are certain investors (particularly development finance institutions) that will insist on some amounts of carried interest being held back. However, if more managers and executives are willing to provide guarantees and perhaps interim clawbacks, we could see a further reduction going forward.

Contacts

- /en/people/o/oneill-brian

Brian O'Neill

Knowledge & Innovation CounselTeam Lead